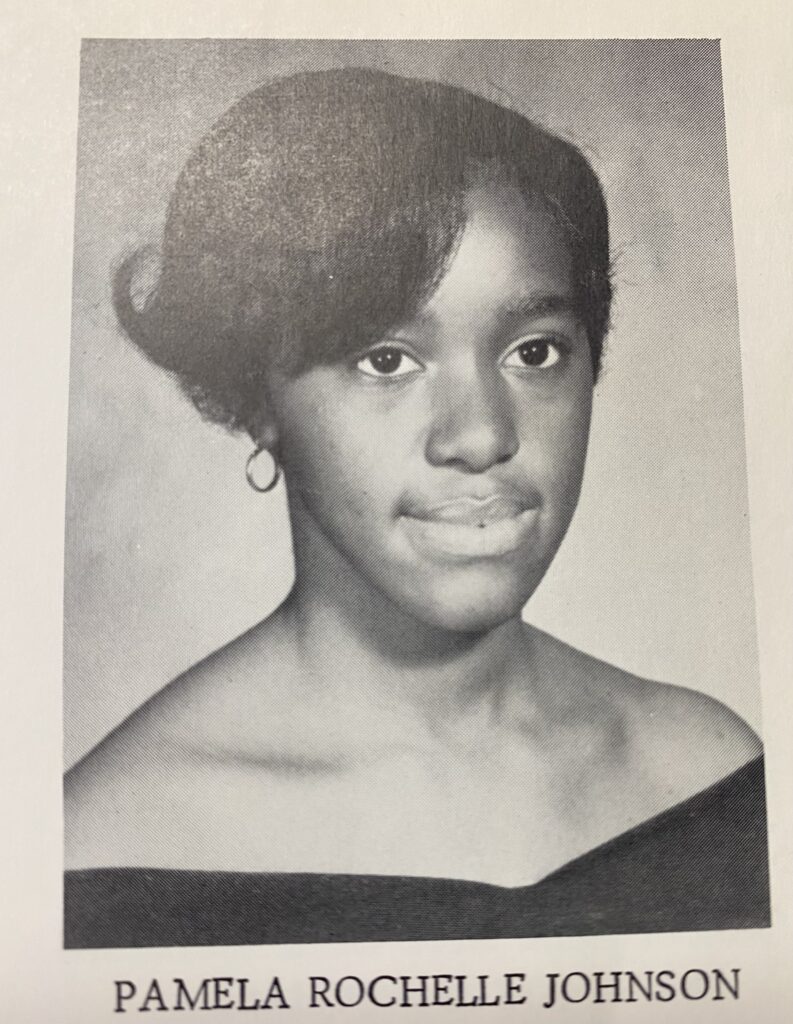

Black History Month may be over, but our attention to Black history continues. I recently sat down with third grade teacher Pam Garvey to discuss her experiences with school integration as a child and the messages she wants to send Black children during Black History Month and beyond.

Pam described her experiences as one of the first Black children to integrate an all-White school in Monticello, Georgia in 1965. She was in sixth grade when she began attending the school which served both junior high and high school students. She said, “ I was very instrumental in marches and sit-ins as a youth. “

“We had a group called Black Youth in Action… I think for the most part these were the kids who actually ended up going to integrate Monticello High School. But I don’t know if we were quite aware of what it meant, the implications, what was expected of us, any of that. I think I was fairly naive at 12 as to how this would work….We had to be bussed. Our bus driver was hostile. The kids on the bus were hostile. And it was frightening.”

Pam described a frightening incident that occurred while walking home from school with a friend. She said, “I was in the 6th or 7th grade…One of the high school students tried to run over us. I can remember it to this day. And I don’t know if he was playing, but we had to dive for the ditch for our lives.”

Pam also described hostility and low expectations from teachers. She said, “The teachers were hostile for the most part because they really didn’t want this. It was being forced on them…The tension was thick…[There was] a difference between how [the teacher is] talking to the White kids and how she’s talking to the Black kids. And I’m pretty sure it came from stereotyping…Those initial years were very hard… I think the trauma had something to do with not performing or not even wanting to perform as well…My math teacher didn’t think I would do well in Algebra II. [I said], ‘But I’m going to college. I need that [class].’ She talked me out of it, and I did not take it…I did take geometry. She told me I wouldn’t do well in that either. But I did prove her wrong. I got an A!”

Pam described how she and her Black peers did not report much of the trauma and mistreatment they experienced. When discussing the student who tried to run her over, she said, “We never told anybody. It was just between us….We didn’t really share those things for some reason. I don’t know why. Here’s an example: I found a diary that I was keeping in the 6th grade and I had none of this stuff in there. I remember talking about the summer, vacation. But as far as the hurt and harmful things, I don’t know why I never put any of that in there.” She continued, saying, “We never told [the principal] that the teachers weren’t trying to teach us. I don’t know why. I guess you just learn to suck it up, and that’s not a good thing.”

Pam described the hostility she experienced, but she also described her resilience and her ability to retain her spirit and not become bitter. She described the support of her family and the importance of her faith. Now, almost sixty years after becoming one of the first Black students to integrate an all-White school, Pam teaches at The Friends School of Atlanta, where approximately 49% of students and 47% of faculty/staff are people of color. She described her experience here as “almost 180 degrees” compared to her experience at Monticello High School. She said, “ I feel validated at this school. I feel appreciated at FSA.”

She described how she strives to teach her students about Black history, highlighting a different Black individual every day during Morning Meeting throughout Black History Month. She said, “This morning we did LeVar Burton [from Reading Rainbow]…We had Thurgood Thursday yesterday. I like these alliterations. And then we had Black Women Wednesday…Our kids are so [interested in science]… I chose Mae Jemison for that reason.”

Pam also described lessons she taught in previous years which sought to teach her students that African Americans’ history and ancestry did not start with enslavement. She taught about the cultures of African societies before the Transatlantic slave trade began. She said, “Our history didn’t start here. We came from great people…We weren’t always oppressed. We had a history before here. I started [there], and then we talked about the middle passage and enslavement. But I wanted them to see that this is not who we always were.”

Pam has taught some of these lessons during Black History Month, which she regards as “a feel good time” where she can “emphasize and celebrate and give particular focus to some of the people who were contributors to the building of this country.” While Pam appreciates Black History Month, her focus on Black history and heritage is not limited to February. She said, “Black history is history, because were it not for the enslaved Africans there would be no history in the United States. We are foundational in the history of the country.”

When asked what message she wants to share with Black students during Black history month and beyond, she said “Just to be able to celebrate who they are in all of whatever it is. I feel like as a child all of this was stifled. For these kids to be able to just celebrate being Black or being whoever they are…just to celebrate and appreciate who you are and to be free…Just be free to love you— your hair, your color, your lips, your feet, all of it.”

We are thankful to have Pam at FSA. We appreciate her sharing some local Black history with us. If you would like to learn more about Georgia’s history with school integration, consider the following resources:

Library of Congress: Six Years after Brown, Atlanta Citizens Discuss Their Schools

Photos: How Atlanta Public Schools Integrated in 1961

Written by Kristen Clayton, Director of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion